For women, heart disease is a deadlier risk than many realize

BY KASHMIRA P. BHADHA, MD, FACC

|

|

|

|

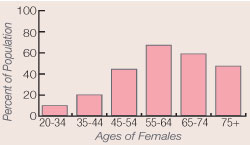

| Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in women |

Heart disease is often thought of as a man’s problem, but heart disease (cardiovascular disease) is the leading cause of death in women. During the last 25 years, the death rate from heart disease for men has steadily decreased, but the rate for women is increasing. When a large group of women took a Gallup survey, most thought they were likely to die from some form of cancer, probably breast cancer. In reality, one out of every three women (and two out of three women 65 years of age and older) will die from heart disease.

The Gender Difference

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is often overlooked or misdiagnosed in women. Although men often have severe chest and arm pain, women’s symptoms are often different and, therefore, overlooked. Women may have shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, cold sweats, fatigue or weakness, feelings of anxiety, loss of appetite, and pain in the upper back, jaw, or neck.

Most women who are admitted to a hospital with a heart attack or cardiac arrest are not aware of their risk or were not diagnosed previously by their physicians as having heart problems. Women have a higher risk of death after a heart attack and are more likely to suffer a second attack. Even in the hospital, women have a higher rate of death after coronary bypass surgery and have more complications following angioplasty.

Women who come to the emergency room with chest pain are treated less aggressively than men. They are less likely to get an electrocardiogram or a blood test for cardiac enzyme measurement (to determine whether they have had an attack) and are less likely to be seen by a cardiologist. They are, however, more likely to receive pain killers (like codeine) or anti-anxiety medications (like Xanax® or Valium®).

Factors that Increase Risk

A woman’s age, hormonal status, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, overweight status, sedentary lifestyle, lipid abnormalities, and family history of heart disease at a young age are important risk factors for CHD in women.

It is important for women to get a complete cholesterol test, which includes a breakdown of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglycerides. A low level of HDL is more predictive of coronary risk in women. Triglycerides appear to influence coronary risk mainly in older women. Every woman 20 years of age and older should have a fasting lipid measurement. A more detailed test (such as the Berkeley Heart Profile), which includes lipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein B and A-1 is recommended if the standard lipid profile (cholesterol test) is normal in women 60 years of age and younger with CHD. Lipoprotein(a) is a useful determinant of CHD in women 66 years of age and younger.

Women are usually diagnosed with CHD at an older age, about five to 10 years after menopause. CHD is unusual in premenopausal women who do not have any other risk factors. A complete hysterectomy, however, both with or without hormone replacement, carries an increased risk of CHD. Lower levels of estrogen cause an increase in LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides but a decrease in HDL cholesterol.

Cigarette smoking is associated with 50% of heart-related ailments (heart attack, angina, sudden death, etc.) in women. Coronary risk is increased even in women who may smoke only one or two cigarettes a day. Compared with nonsmokers, the probability of a heart attack is increased 600% in women and 300% in men, but it is never too late to stop smoking. Most of the increased risk from smoking is eliminated within two to three years after quitting.

Central obesity (a waist-hip ratio of > 0.9 or a waist circumference of more than 35 inches) is more predictive of risk than the total body weight or simple body mass index in women.

In a future issue of this magazine, diagnostic tests, treatment options, and CHD risk-reduction techniques currently available will be discussed.