BY RAUL MITRANI, MD

|

|

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in the United States, affecting 2.4 million people. The incidence of AF increases with age; it is estimated that by 80 years of age 8% of patients have or have had an episode of AF.

AF is a disease associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Patients with AF are at risk for thromboembolic events and worsening cardiac function that could lead to congestive heart failure. Many patients have fatigue, tiredness, or other symptoms associated with loss of mechanical atrial function. AF is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with congestive heart failure. Therefore, AF is a major clinical problem.

This review focuses on current therapies of AF and incorporates recommendations from the 2006 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee (ACC/AHA/ESC) Practice Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation published in August 2006. In particular, the discussion will focus on management issues in heart rate control, prevention of thromboembolic complications, and rhythm control to normal sinus rhythm.

Definitions

AF is an atrial arrhythmia characterized by rapid, uncoordinated atrial activity or mechanical function.

Persistent AF is AF that persists unless active medical measures are employed to electrically or pharmacologically cardiovert the patient back to normal sinus rhythm. Generally, AF duration greater than seven days is classified as persistent.

Paroxysmal AF is AF that starts and stops spontaneously.

Lone AF is AF in a patient without valvular heart disease, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, or a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, prior cerebral vascular accident (CVA), or thromboembolic event.

Initial Evaluation

Although most patients with AF have chronic heart disease that causes AF, there are patients with reversible causes. These include excess alcohol intake, recent cardiothoracic surgery, hyperthyroidism, pulmonary embolus and other pulmonary diseases, Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome, and some metabolic disorders. For these patients, treatment of the underlying disorders can eliminate the AF. Therefore, identification of reversible causes should be part of the initial evaluation.

It is important to classify patients according to the presence or absence of other heart disease. Additionally, patients should be classified according to whether the episode is the first, whether the AF is paroxysmal or persistent, and to what extent the AF causes symptoms. The initial evaluation also involves documentation by electrocardiogram of the AF. In general, initial evaluation includes a comprehensive history and physical exam, measurement of thyroid function, and an echocardiogram.

Additional monitoring with event recorders or Holter monitors is recommended to quantify the AF, characterize the ventricular response and rate, and correlate symptoms to arrhythmias. Stress testing or other ischemia workup is indicated only in patients who have other conditions mandating such testing. Diagnostic electrophysiology studies are usually not indicated unless there are concurrent arrhythmias (atrial flutter, supraventricular tachycardia) or to guide primary ablation therapy.

Management of AF

Treatment of AF involves three objectives:

- Prevention of thromboembolism

- Ventricular rate control

- Restoration and maintenance of normal sinus rhythm (rhythm control)

Prevention of Thromboembolism

Antithrombotic therapy (warfarin) to prevent thromboembolism is recommended for most patients with AF, except those with lone AF or those with anticoagulation contraindications. Warfarin is recommended for all patients with moderate risk factors, including advanced age (65 years of age and older), hypertension, history of congestive heart failure, impaired left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction <35%), diabetes mellitus, or past history of transient ischemic attack (TIA)/CVA or other thromboembolism. In the absence of mechanical heart valves, the target international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 to 3.0. There is no difference in anticoagulation strategies in patients with paroxysmal versus persistent AF.

As per the recent ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation, aspirin therapy may be substituted for warfarin in select lower-risk patients, depending on the risk/benefit ratio. Additionally, in patients younger than 60 years of age with lone AF, warfarin therapy is not recommended.

Newer anticoagulants to replace warfarin are currently undergoing trials in the United States.

Rate Control

|

|

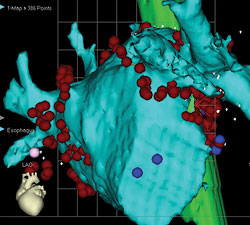

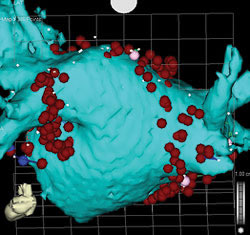

| Anterior (above) and posterior (below) views of CT scan-guided reconstruction of the left atrium during atrial fibrillation ablation. The tree-like branch structures emanating from the left atrium represent the pulmonary veins. The red dots represent ablation lesions encircling the pulmonary veins. In one view, the bright green structure represents the esophagus, which sits right behind the left atrium. | |

|

Acute control of ventricular response in patients with AF and rapid response is often achieved with beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers (diltiazem, verapamil), or digoxin. The choice of agents to control ventricular response depends on comorbidities. For patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, beta-blockers are avoided. For patients with congestive heart failure, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers are used with caution. Digoxin is usually not effective as a single agent but is used as a second- or third-line agent. Intravenous amiodarone is often useful to control heart rate in patients with AF when other measures are unsuccessful or contraindicated.

Chronic rate control is very much achievable with the same medications, either as solo agents or in combination (beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium blocker, digoxin). During office visits, the adequacy of rate control should be assessed at rest and during exercise. Many elderly patients with underlying sick sinus syndrome may develop symptomatic bradyarrhythmias as a consequence of rate control treatment. In this scenario, a pacer is implanted to prevent bradyarrhythmias and to allow for treatment of AF.

The deleterious effects of having rapid rates to AF include fatigue, palpitations, and shortness of breath. A tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy may develop, leading to congestive heart failure. In patients with already compromised left ventricular systolic or diastolic function, the presence of AF with rapid rates leads to worsening of the congestive heart failure. There are occasional patients who have persistent rapid rates despite medical therapy; in these patients, it is reasonable to perform an atrioventricular-nodal ablation and implant a pacer.

Rhythm Control

Rhythm control in patients with AF refers to a strategy of converting a patient in persistent AF to normal sinus rhythm and to one of using drugs or nonpharmacologic techniques to maintain normal sinus rhythm in patients with either persistent or paroxysmal AF. Rhythm control is preferred in many patients with AF due to the presence of symptoms of fatigue, malaise, shortness of breath, and palpitations, even if they have adequate rate control. Additionally, it is thought that converting and maintaining normal sinus rhythm is beneficial in the long term, although studies done to date have not supported this notion.

it is expected that radiofrequency ablation will be used to

cure an ever-expanding population of patients with AF."

Cardioversion of AF

Cardioversion of AF to normal sinus rhythm involves a two-step process. The first step is to ensure that such cardioversion does not place patients at undue risk of thromboembolic complications. Cardioversion is thought to involve acceptably low risk of thromboembolic complications in many but not all patients with AF lasting less than 24 to 48 hours or in patients who have documented therapeutic INRs>2.1 for more than four weeks. In other patients, a transesophageal echocardiogram should be performed to rule out left atrial appendage thrombus prior to cardioversion. After cardioversion to normal sinus rhythm, patients should receive adequate anticoagulation for at least four weeks and, in many instances, for a considerably longer duration of time, depending on other clinical factors.

The actual process of cardioversion is often accomplished by electrical cardioversion using DC energy between 50 and 360 joules. Biphasic shocks are more effective than the older-style monophasic shocks. Chemical cardioversion is often accomplished successfully in a lower percentage of patients using drugs such as amiodarone, ibutilide, procainamide, or others. In general, rate-slowing drugs, such as beta-blockers, calcium blockers, and digoxin, do not directly induce cardioversion from AF to normal sinus rhythm.

Maintenance of Normal Sinus Rhythm

As discussed above, treatment of any precipitating or reversible causes of AF is the initial recommendation. In most patients, no cause is identified. Therefore, an antiarrhythmic drug is often recommended. Many antiarrhythmic drugs are associated with side effects, toxicities, and potential for ventricular proarrhythmia. Therefore, these drugs are usually carefully chosen and, in many cases, initiated under a monitored setting.

Class I antiarrhythmic drugs, especially flecainide and propafenone, are generally contraindicated in patients with coronary artery disease but are recommended agents in patients with lone AF or patients with hypertension without left ventricular hypertrophy and otherwise no significant heart disease. Amiodarone is considered the most effective drug, but significant long-term side effects and toxicities limit its use to patients with heart failure or coronary artery disease. Sotalol and dofetilide are also used in coronary artery disease and heart failure (dofetilide), but inpatient initiation of these drugs is mandatory due to significant risks of ventricular proarrhythmia/torsades de pontes.

Rate vs. Rhythm Control

Studies to date do not support a routine strategy of rhythm control rather than rate control in patients with minimally symptomatic or asymptomatic AF. The AFFIRM trial examined more than 4,000 patients with AF who randomized to a strategy of either rate or rhythm control. There was no advantage to rhythm control compared with rate control. In this trial, only 65% of patients in the rhythm control arm were in normal sinus rhythm (NSR) and approximately 35% of patients in the rate control arm were in NSR. Post hoc retrospective analysis showed that patients in NSR (in either the rhythm control or the rate control arms) actually did better in terms of survival compared with patients in AF. Therefore, the data suggests that we still have imperfect and somewhat risky therapies for rhythm control which may counterbalance the benefit of being in NSR. In current clinical practice, rhythm control is advisable for patients who are symptomatic or have other clinical sequelae with AF.

Radiofrequency Ablation for AF

The initial use of radiofrequency (RF) ablation for patients with AF was restricted to ablation of the AV node to cause heart block and placement of a permanent pacer. This strategy was and, to some extent, is still used in patients with AF with rapid ventricular response refractory to medication. This strategy, however, neither eliminated the underlying AF nor reduced the need for anticoagulation therapy to prevent thromboembolism.

As discussed above, antiarrhythmic drugs have limited efficacy at maintaining NSR and are associated with potential side effects and toxicities. Therefore, RF ablation has gained popularity as a technique to actually cure patients of AF. Because most patients have AF initiating in the left atrium in or around the pulmonary veins, the technique of RF ablation usually involves electrical isolation of the pulmonary veins vs. encircling lesions around the pulmonary veins.

As shown in the figure on page 15, RF lesions were placed around the ostia of the right and left-sided pulmonary veins. Other lesion sets in the right or left atrium are sometimes necessary to achieve success. The long-term success rate of this approach is between 70% and 90%, depending on the patient population. Early recurrences of AF or atrial flutter in the first 3 months post ablation does not necessarily predict long-term failure.

The use of RF ablation to cure AF should only be performed in experienced centers, because the potential for serious complications may approach 5% to 6%. These complications include cardiac perforation or tamponade, pulmonary vein stenosis, and thromboembolic complications, such as myocardial infarction or cerebral infarct. Rare complications such as atrioesophageal fistula formation can lead to death.

Nevertheless, in carefully selected patients with symptomatic AF refractory to at least one antiarrhythmic drug, the use of RF ablation to cure AF is a reasonable therapy that offers patients the opportunity to live free of the symptoms of AF and the use of drugs and anticoagulants.

Conclusions

AF is associated with major morbidity and increased risk of mortality. Treatment algorithms are geared toward rate control, rhythm control, and prevention of thromboembolic complications. There is no clear mortality or quality of life advantage to rhythm control vs. rate control in patients with minimal to no symptoms of AF. However, in symptomatic patients with AF, a strategy of rhythm control is often necessary. The use of antiarrhythmic drugs is limited by side effects, potential toxicities, and inefficacies of the drug. RF ablation as a curative procedure is gaining acceptance as a second-line therapy. With improvements in technology and operator experience, it is expected that RF ablation will be used to cure an ever-expanding population of patients with AF.

Suggested Reading

- Fuster V, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:854–906.

- AFFIRM Investigators. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. NEJM 2002; 347:1825–33.